last authored: June 2013, Brandon Cook; July 2014, Julianne Zandberg

Introduction

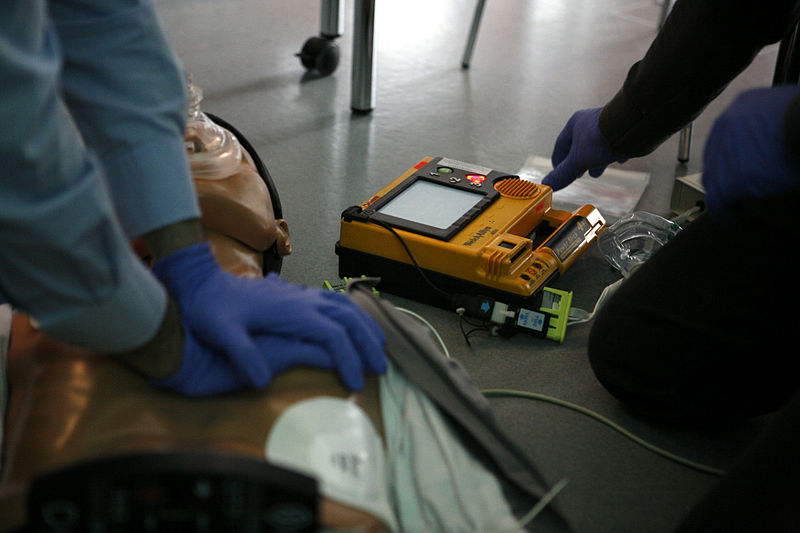

CPR with AED simulation

courtesy of Rama, wikipedia

Basic life support (BLS) is the provision of care to an unresponsive patient. The mainstay of BLS is cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR. While trained and equipped health care providers can provide more extended care through advanced cardiac life support (ACLS), “the foundation of successful ACLS is good BLS” (American Heart Association). Immediate bystander CPR given to an out of hospital, witnessed cardiac arrest increases the survival rate to 50% (American Heart Association).

The American Heart Association emphasizes a series of actions that should be taken known as the chain of survival. The links include (American Heart Association, 2010):

- Immediate recognition of cardiac arrest and activation of the emergency response system

- Early CPR with an emphasis on chest compressions

- Rapid defibrillation

- Effective advanced life support

- Integrated post–cardiac arrest care

While for many years teaching was ABC – airway, breathing, circulation – in 2010, the American Heart Association published new guidelines for approaching an unresponsive patient, with the order now being CAB – circulation, airway, and breathing.

This article details the considerations for providing BLS as a health care provider, but the main aspects remain the same regardless of level of training. Lay responders should not attempt a pulse check, and should activate emergency services upon discovery of an unresponsive person.

Approaching the Patient

Check the Environment

When approaching any scene or being approached by a patient, it is highly important to consider what aspects of the situation could pose a danger to you or others. Carefully observation can also help to determine the mechanism of injury, and environmental signs may give you clues as to the patient’s condition.

Also make a quick assessment of the appearance of the patient, and consider any additional resources that will be required.

Check the Patient

Rapidly check responsiveness by tapping the patient and speaking loudly into each ear. At the same time, survey the patient for obvious signs of normal breathing, such as chest rise and fall or sounds of air entry. Occasional gasps are not considered normal breathing.

If the patient remains unresponsive, and/or is not breathing normally, you or another provider should activate emergency response (call 911 if out of hospital, or activate code blue if in hospital) and get a defibrillator.

Assess for a Pulse

Health Care Providers should then feel for a carotid pulse for no more than 10 seconds while simultaneously looking for breathing . If there is no definite pulse felt, initiate the cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) algorithm. If there is a pulse, initiate the artificial respiration (AR) algorithm.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

CPR should provided in the CAB order:

C – Circulation: Begin with 30 chest compressions. Place the heel of the bottom hand in the middle of the sternum, approximately at the nipple line, and place the heel of the top hand parallel to the bottom. Push hard and fast, at a rate of at least 100 compressions per minute, (approximately 18 seconds for 30). Keep elbows straight, and shoulders above the sternum. Ensure compression depth of 2 inches in adults, allowing the chest to recoil completely in between each compression. Full recoil is required to allow adequate perfusion of the coronary arteries and brain.

A – Airway: After completing 30 compressions, open and check the patient’s airway. There are two techniques that may be used:

- Perform a head tilt-chin lift by placing one hand on the patient’s forehead and the other under their chin and lifting so that the patient’s head is tilted back. This technique is used under normal circumstances.

- The modified jaw thrust may be used by health care providers if there is concern that the patient may have a cervical spine (C-spine) injury. Place your thumbs on the patient’s cheek bones and your fingers at the back of the patient’s jaw. Lift so that the jaw is moved forward and the tongue is lifted off the back of the throat. If the jaw thrust does not adequately open the airway, a head tilt-chin left should be used even in the case of a potential spinal injury.

Look in the mouth and ensure that there are no obstructions or fluids. The unconscious patient is unable to protect their own airway, so it is the job of the provider to ensure its patency. The techniques listed are further described under basic airway management.

B – Breathing: While maintaining an open airway, give the patient two breaths, watching for chest rise and fall. Consider how much air the patient’s lungs will hold, and do not over ventilate. If the breath does meets resistance, readjust the head by performing another head tilt-chin lift and attempt to ventilate again. If the breath still does not go in, follow the procedure for an airway obstruction.

Breaths can be given by the following methods:

- mouth-to-mouth

- mouth-to-nose

- mouth-to-stoma

- mouth to barrier device

- bag-valve mask

Always use personal protective equipment, such as a face mask or shield. Compression-only CPR may be performed when barrier devices are not available. For health care providers, basic airway supports and a bag-valve-mask (BVM) with oxygen should be used where available, as described under basic airway management, until an advanced airway can be secured.

Continue in a ration of 30 compressions to 2 breaths until an AED or manual defibrillator arrives. Minimize breaks between CPR; the two breaths should be given in ten seconds or less. Ensure the airway is open before every breath. Every time there is a pause, coronary perfusion drops significantly.

Artificial Respiration (AR)

If the patient has a pulse but is not breathing, begin to provide breaths as described above. Watch for chest rise and fall, and do not over ventilate the patient. Breaths should be given at a rate of:

- Adult – every 5-6 seconds

- Child – every 4-5 seconds

- Infant – every 3-4 seconds

Re-assess the patient’s pulse every 2 minutes after beginning AR, and initiate CPR if no definite pulse is found.

Airway Obstruction

If the attempt to ventilate the patient is unsuccessful after readjusting the head once, assume there is an obstruction and begin doing chest compressions in the same manner as CPR.

After 30 compressions, open the airway using a head tilt-chin lift and look to see if the obstruction has dislodged. If an object is visible, remove it. If an object is removed, resume chest compressions and breaths at a ratio of 30:2.

If there is no visible object, attempt to ventilate the patient. If the breath goes in, give another one. If the breath does not go in, do not readjust the head again, go directly back to chest compressions.

Continue in a ratio of 30 compressions to 1 breath, ensuring to check the airway each cycle, until the object becomes dislodged, or other health care providers arrive. Laryngoscopy or bronchoscopy may be performed in order to visualize and remove the blockage.

Infant and Child Considerations

Definitions:

Child – CPR: age 1- puberty;

AED – age 1-8

Infant – CPR/AED: less than the age of 1

The size of infants and children require adjustments to BLS. Changes for children include:

- A smaller volume of air – just enough to make the chest rise – is given with each breath.

- Compressions should be 1/3 of the chest depth, which is approximately 2 inches/5 cm in children.

• The ratio remains 30 compressions : 2 rescue breaths, unless two rescuers are present, which changes the ratio to 15 compressions : 2 breaths - A lone rescuer should perform 5 cycles of chest compressions before leaving to activate emergency services

- With artificial respiration, breaths should be given at a rate of 1 breath every 4 seconds.

- An AED with a pediatric dose attenuator system or a manual defibrillator should be used if available. If an AED with a dose attenuator is not available, an AED without a dose attenuator may be used instead. Energy doses for children typically start at 2 J/kg and increase to at least 4 J/kg.

Changes during care of infants include:

- An infant’s head does not need to be tilted as far back as an adult’s or child’s.

- Breaths are mere ‘puffs’, and should be given every three seconds

- The brachial artery is used for pulse checks, instead of the carotid artery.

- Infant chest compressions are not the same as adult or child compressions, and depend on the number of rescuers available. Single rescuers use two fingers, placed on the centre of the chest just below the nipple line. Compress the chest 1/3 to 1/2 the chest depth, or approximately 1.5 inches/4cm. Ensure a solid surface below the infant. If two rescuers are present, one will wrap two hands around chest, with thumbs placed on the centre of the sternum and perform compressions at a rate of 15 to 2 breaths. Switch roles every five cycles.

- A manual defibrillator is preferred for infants. If one is not available, an AED with a pediatric dose attenuator should be used. If neither is available, an AED without a dose attenuator may be used.

Defibrillator Use

main article: defibrillation/cardioversion

Early defibrillation is critical to cardiac arrest survival; therefore, when an automated or manual defibrillator arrives, the pads should be applied immediately, even if the provider is in the middle of a cycle of compressions.

Before delivering a shock, ensure that there are no rescuers or bystanders touching the patient and that oxygen sources are not blowing oxygen towards the patient’s chest.

It is important to minimize interruptions in chest compressions before and after each shock. Compressions, not rescue breaths, should immediately precede each shock. Resume CPR immediately after defibrillation. Because new spontaneous heart rhythms tend to be slow and inadequate for perfusion, it is necessary to continue CPR for several minutes until adequate heart function resumes.

CPR with an Advanced Airway

main article: advanced airway management

There are a variety of artificial airways which can be used to maintain an open airway between the lungs and mouth/nose.

Once an advanced airway (endotracheal tube, laryngeal mask airway, Combitube) is in place, one rescuer should continue compressions at 100 per minute, while the other rescuer provides one breath every 6-8 seconds. There is no need to pause compressions to deliver ventilations through an advanced airway. Rescuers should change roles every two minutes to prevent fatigue.

Additional Resources

2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care

Berg RA, Hemphill R, Abella BS, Aufderheide TP, Cave DM, Hazinski MF, et al. Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010 Nov 2;122(18 suppl 3):S685–S705.1.

Field et al. 2010. 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science. Circulation. 122: S640-S656